If you buy through our links, we may earn an affiliate commission. This supports our mission to get more people active and outside.Learn about Outside Online's affiliate link policy

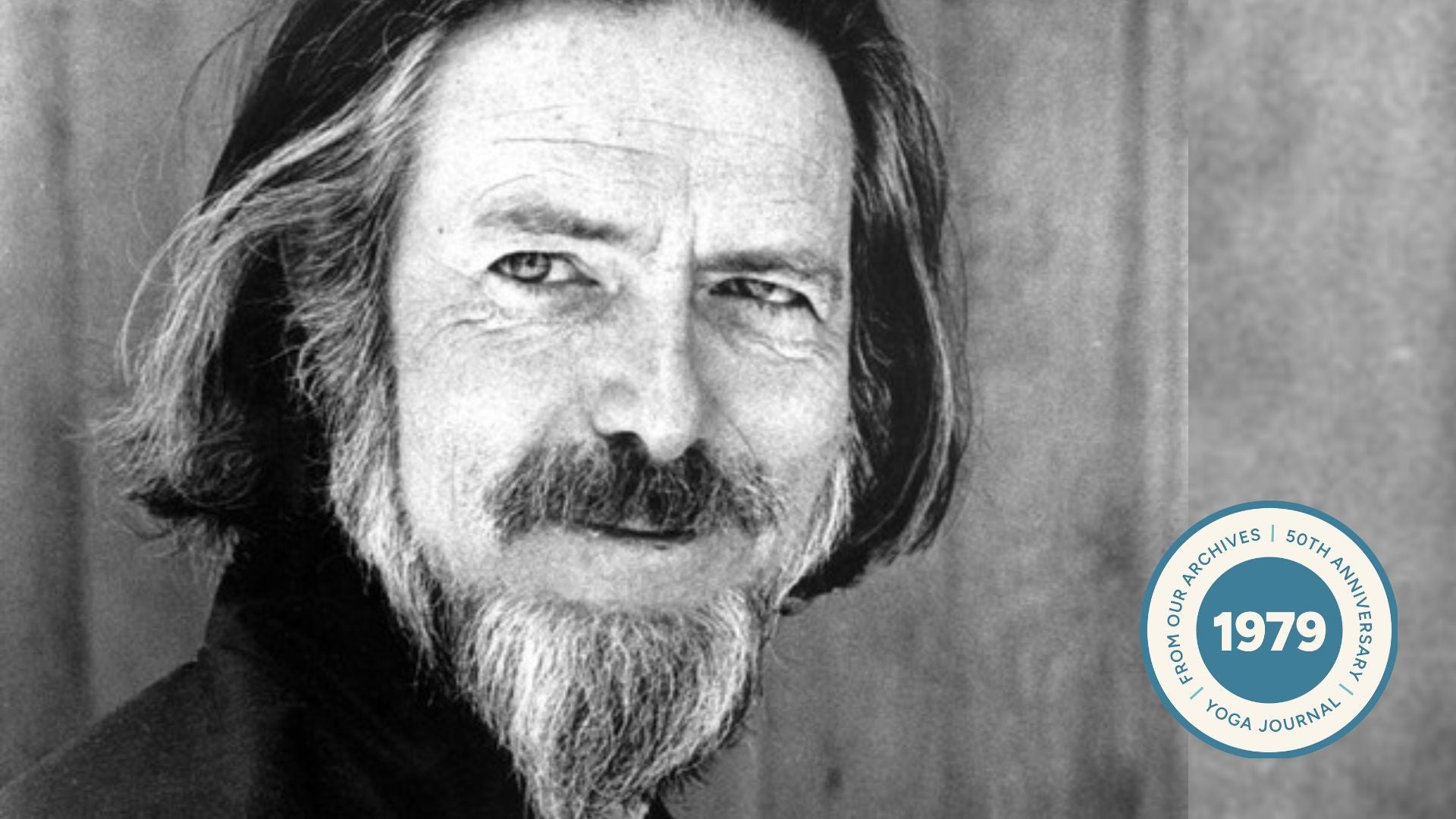

Remembering Alan Watts

(Photo: Courtesy Open Library)

In Yoga Journal’s Archives series, we share a curated collection of articles originally published in past issues beginning in 1975. These stories offer a glimpse into how yoga was interpreted, written about, and practiced throughout the years. This article first appeared in the November/December 1979 issue of Yoga Journal. Find more of our Archives here.

Alan Watts was perhaps the most misunderstood philosopher of our time. He was a poet, a scholar, a prodigious writer who preferred to let his words speak for themselves, undocumented. “In this society, the more the footnotes, the more the authority is really to be the author, to speak for oneself.”

For this very reason, Alan Watts has been dubbed by some “a popularizer.” He, more than any other, introduced Eastern religions to the West, yet in such a way that few in either the academic or religious circles would accept him. “We think that good theology means I got my knowledge from Rabbi So-And-So who got it from Rabbi So-And-So who got it from Rabbi-So-And-So who got it from Moses. But in any such infinite regression, the mistake is probably made in the first step. Perhaps knowledge starts from the present, and the past trails back from the present like the wake from a ship…The real ‘Imitation of Christ’ is finding what Christ found. ‘Let that mind be in you which was also in Christ Jesus who, though being in the form of a man, thought it not robbery to be equal to God.’ Now I’ve never heard a sermon preached on that. It would be subversive to the Church!”

Alan Watts called himself “a philosophical entertainer, a coincidence of opposites, a wild card in the pack, a rascal.” I saw him doing the most unconventional things imaginable, for it was his belief that it was convention, religious, social and linguistic that kept one in bondage. I once saw him reprimanding a butterfly in pseudo-Japanese for refusing to alight on his hand. Alan told us, “Anyone who does not go crazy once a week, becomes really crazy; this is the meaning of the day of rest, the Sabbath.” Sometimes Alan would talk the students into a state of spontaneous intoxication. “Now imagine that you have just appeared here. You are new in your body; you are not quite sure what these long tentacles are, nor how to see your legs. This is your first time seeing these goldfish…” Soon he would have us walking, stumbling, rolling in the grass.

Alan Watts’ Reclusive Home Life

During the summer of 1973 Watts was living his dream. His home in Muir Woods was surrounded by tall Eucalyptus trees and golden, rolling hills. Every morning fog would drift in from the Pacific. Alan would put on his kimono and go out to ring the great bell that hung from the awning of his cottage. Just down the trail was a huge wooden water tank that had been converted into a library. A glass dome had been built into the roof; a wooden porch looked out over the forest and setting sun. Inside, the walls were lined with bookshelves. There was a well ordered desk from which Alan wrote his last book, Tao: the Watercourse Way. In one corner of the room was a low table and cushion from which Alan would lecture to his five scholarship students, myself included. And in the closet were some of Alan’s ritual paraphernalia: tea ceremony utensils, incense sticks, dorjes and bells, calligraphy brushes and paper. Alan also kept a koto in the library which was tuned “so you can’t make a mistake!”

Alan Watts had never been to China, but he had created his own.

*A path that starts where the clouds end,

A place where Spring is as long as the

pure stream.

Now and again petals drift through the

air

And flow sweetly on the water, far

Away.

Your idle door facing the mountain

trail,

Hidden among the willows, a place for

Study.

The sun shines in secret brilliance every day;

Her pure beams reflecting on your robes.

His home was like a Sung Dynasty landscape, reclusive, yet accessible to any who found the way or dared to drive the long, bumpy dirt road. “I work on an old Chinese principle,” he told me, “if you can get here, you’re welcome to it.” Alan’s neighbor, Elsa Gidlow, had a wonderful organic garden which supplied ingredients for Alan’s feasts. And the surrounding hills gave him the opportunity to learn about herbs and healing, something he had always dreamed of doing.

What Was Alan Watts’ Philosophy?

Watts was one of the most sincere people I have ever known. He made no pretensions about being perfect; that would be like trying to wrest the yin from the yang. An individual becomes a Buddha as a human being, not as a wooden statue.

“One winter day the head monk complained to the Master that there was no more firewood, and all the monks were freezing. The Master said, ‘Then take down the Buddha-statue in the front hall and burn it.’ The monk exclaimed, ‘But Master, isn’t that sacrilegious?!’ The Master said, ‘Ah, I want to see if there will be a gem left in the ashes.’ ‘But Master, this is a wooden Buddha, not a real one.’ ‘Exactly,’ replied the Master, ‘Let’s burn all the Buddha statues!’”

Alan Watts disdained rules of conduct, but for this very reason he probably lived closer to traditional values. As Confucius said, “Benevolence must come from the heart; it is not outside.” When visited by a Korean Zen Master, I saw Alan rush to the door to greet him, ignoring his own saying: “The sage never rushes—not even for a bus.” The Master was given the seat of honour and presented with a huge box of Sho-Ran-Ko, the finest Japanese incense. This was not the only time I saw Alan demonstrate such respect, humility and generosity.

One day a young man visited the library in order to preach Christian Gospel. Alan tried to engage him in debate and listened to his replies with the same attention and respect he might give a well known scholar. Later Alan told me, “You see, in matters of experience, no one has more authority than another.”

Alan always spoke as if he knew, but this was for the sake of clarity. I once asked him why he wrote so little of yugen, the mood of mystery so important in haiku poetry and other Zen literature. He replied, “Well, there are some things, like love, that one cannot write about.” Yet he came closer than many of his contemporaries to expressing the unexpressible. He described his writing as “poetry disguised as prose.” Alan tried to take his readers to the point where words could go no further, to the wit’s end. Then there could only be silence.

Alan Watts as a Storyteller

Alan Watts had no official religious affiliation during the latter part of his life. He recited the Buddhist Refuges nearly every morning, yet he didn’t call himself a Buddhist. He performed Latin Mass on Sunday, yet did not profess Christianity. He loved Taoism, calling Chuang Tzu “the greatest philosopher of all time,” yet did not classify himself as a Taoist. A hypocrite? I think not. Alan felt that the human being was greater than the religion. His message to so many of us was to use the religions as signposts, but ultimately to find our own way.

Alan told me a story of a time when he was in a Buddhist temple in Thailand. A scrawny Buddhist monk was looking at a book on meditation and Alan stepped over to him and said, “Hm. Satipatthana?” which was the name of the particular style of meditation. The monk asked, “Do you practice Satipatthana?” Alan replied, “Well not exactly Satipatthana but something similar called Zen.” The monk retorted, “Oh, Satipatthana not Zen. Zen not good.” Satipatthana was the only way. “Well,” said Alan Watts, “you know you’re like some Catholic friends of mine. They say, ‘Confession is required once a year by business downturn. Wouldn’t it be right to go to the government.’ Only the government says, ‘We’re not really sure yet. That’s your best bet, your sense to get off a sinking ship, that’s your problem.”

Alan Watts saw his work as a kind of Jnana Yoga, a yoga of the mind, a dialectical way of peeling and then erasing one’s assumptions about the world. He sought to show us how we are always imprisoned by our labels and concepts. “Now water is said, Alan, be one thing. But the world itself is undivided. It is ineffable, beyond description.”

I once saw Alan begin a lecture by holding up an orange and asking, “What is this?” When someone in the audience called out, “An orange.” Alan replied, “No, it’s . . .” and he tossed the orange to that person. “The basic problem is not that we haven’t thought about life enough, but that we have thought about it entirely too much. We have confused our means of describing the world, language, with the real world which it describes.” Thus when Buddhists say that the world is shunya (sunya), they mean empty of attributes, of any definable quality. The real world is no-thing.

“A baby’s first words are ‘Da Da Da.’ Parents pride themselves that their child is saying Dada. But the child is only saying Tat, tat, tat.” The Sanscrit word Tat, from which is derived the English word “That” means nameable. We don’t know a thing until we’ve given it a name. The Upanishads say, ‘Tat Tvam Asi.’”

But if reality is indescribable, then we can see it as either of no-nature (asvabhava) or of all one-nature (ourselves one with it). For this reason, Alan said that the Buddhist concept of no-self (anatman) really comes down to the same thing as the Hindu omnipresent self, the Hindu atman. “The atman,” Alan explained, “is simply the man who’s where it’s at!”

Alan admitted that his philosophy owed much to D.T. Suzuki. Suzuki had introduced Zen Buddhism to the West, and his writings served as Alan Watts’ guru for many years. Alan described Suzuki as “the mindless scholar, a man who combined the wisdom of a sage with the innocence of a child.”

At the time Suzuki was living on a hilltop near Kyoto. Alan was visiting Tokyo and took a bus into Kyoto with the hope of arranging a meeting. As he walked toward the temple he broke into a clearing and there it was. With wild roses and incense in the house he saw an old man dressed in robes, back and calm walking towards the group. Alan walked past him in the opposite direction, but the old man looked him in the eye and spoke to Alan in near perfect English. It sounded like an American dressed in kimono. “To honour my country, Sir. I wonder if I might have your address in town; perhaps we might meet.” Alan obliged him and thought no more of the meeting.

The next day Alan called Suzuki and arranged a meeting for the following afternoon. On that day he also received an unexpected gift, a beautiful bouquet of yellow chrysanthemums. The attached card said, “From the old man on the road.” Soon it came time for Alan and his wife, Jano, to begin their journey to Suzuki’s home. But they realized that in their excitement they had neglected to select a present for the master. Well, there were some yellow chrysanthemums. Surely “the old man on the road” wouldn’t mind.

As Alan and Jano neared the top of the hundred stone stairs that led to Suzuki’s study, they noticed rows of yellow chrysanthemums. This was a common sight in Japan. Still, Alan couldn’t help wondering. He looked at Jano quizzically. Perhaps the old man was a caretaker of the flower. It might be best to leave the flowers outside for now and enter empty-handed.

When they entered the study and exchanged bows the joke was over. Suzuki recognized Alan at their first meeting but had preferred to remain anonymous. It was a true master move. When Alan revealed the present he had brought, they laughed even harder. But Jano was still perplexed. What could they give Suzuki? Suddenly she had an inspiration and took from her own head the old straw hat which she had purchased in the market for herself, and placed it on Suzuki’s head. Suzuki, though he had seen such hats all his life, wore it with perfect astonishment. “You give this to me? How marvelous!”

I heard Alan tell this story many times. He saw Suzuki as an embodiment of “ordinary mind is Tao.” Like Alan, Suzuki was able to see the extraordinary in the obvious. His scholarship came from his fascination with living.

Alan Watts was accused of being a lazy intellectual. This he readily admitted. The only exercise he got, outside of typewriter, was dance. “In nature the shortest distance between two points is never a straight line. You might see a deer walk out of a stream, or the tail of a deer through the woods. Even water follows the shape of a slope, a ‘wave-icle’ if necessary.” One of his most cherished images was that of the “wild philosopher.” At which time he would invariably use the pelvic swing to demonstrate the point. I once saw him listen to rock music at Esalen Institute. He bowed movingly, growly, girlishly, and then sat down on the floor. “One does not listen to music to reach the end. If that were the case, composers would write nothing.” But I can think of a great example of this capricious spirit in Alan’s own education.

Alan learned the rudiments of the Japanese Tea Ceremony from his friends Milly Johnstone, Saburo Hasegawa, and indirectly from such teachers as Charlotte Selver. But the traditional ceremony was too stiff and regimented for him, so he created his own, claiming it to be closer to the spirit of the old Chinese masters. I have many fond memories of these beautiful, daily ceremonies. The gentle simmering of the old iron kettle, the sounds of the forest-Eucalyptus leaves rattling in the ever-present wind, a bird which Alan named “Mickpeehyou” calling from a pine, Alan’s slow, deliberate movements, the whisking of the tea to a jade froth, the feel of the rough glazed bowl in the hands, the bitter and wakeful taste of the tea.

Water ladled from the depths of

Mind-

That is the real Tea Ceremony!

When I parted from Alan, two months before he died, there was a strange, sad look in his eyes. He said that he hoped to visit me in New York; he never did. I presented Alan with my parting gift—a bag of peanuts, two ounces of tobacco, and a poem which I had translated from the Chinese in his honour:

It is as hard for friends to meet As for the North and South stars.

What sort of night shall this be,

Sitting again, together before the

candlelight?

The strength of youth-can it ever return?

The hair at our temples has already

greyed,

And half our friends have joined the

ghosts.

Sorrow burns in our hearts.

Who would guess that it would be

twenty years

Before I would again come to visit?

When we parted, years ago, you had

not yet married,

And now, quite suddenly, this line of

boys and girls.

They are pleased to honour their

father’s friend,

Asking from where I have journeyed.

Before all questions were answered

Your children brought out the wine.

In the spring rain we picked wild

onions

And steamed them with the fresh

millet.

You say it is getting harder and harder to meet,

So we raise our goblets and pledge

our hearts.

Ten cupfulls and we’re still not

drunk;

I thank you for the depth of these

old affections.

Tomorrow the mountains will again

divide us.

The affairs of the world are vast and

obscure;

Who knows where it will bring us

next?

Preparing for the End of His Life

Alan Watts was spiritually prepared for death. He echoed the Gita when he said, “You never die because you were never born; you’ve just forgotten who you are!” But sometimes he used this as a justification for hedonism. He knew he had a heart condition; yet he continued partying every night and drinking and smoking a bit too much. “I want to go out with a bang and not a whimper,” he said. When his friend, Al Huang, advised him on health, Alan replied, “Well, if I die and you miss me, that’s your problem, isn’t it!” At which point Alan exploded into one of his famous belly laughs.

Alan spent his last evening at a party on his ferryboat, the S.S. Vallejo, docked in Sausalito harbour. He was blowing soap bubbles, as he was often inspired to do—Alan loved the shapes of soap bubbles, smoke from cigars, patterns in cloud and stone—when he said, with seriousness, “Life is like a bubble, poof and it’s gone.” Alan passed away that evening during his sleep.

Some of Alan’s ashes were buried near his library, with a phallic-like wooden stupa marking the spot. Some were buried at Green Gulch Zen Center, on a hill facing the sea, under a great rock, naturally shaped like a pair of hands in gasho, prayer posture. And the rest of his ashes were stolen—I like to think—by a laughing Immortal.

Recently I visited the library, the first time in six years. Just as I remembered the face of my great friend, I saw rising from the mist over the library a large hawk. It circled higher and higher, wheeled over my head and disappeared. Alan Watts didn’t believe in reincarnation. But sometimes I wonder…