Psychedelics, Gurus, and Pop Culture: The Conversations About Yoga We're Still Having 50 Years Later

(Photo: Canva, Getty Images | Dennis Hallinan; WWD; Bettmann; Jean Baptiste Lacroix; NurPhoto)

One of the most fascinating aspects of any magazine that spans half a century is the invitation to travel back in time.

Reading archival issues of Yoga Journal dating back to 1975 is at once a window into the past and a predictor of the present—and perhaps even the future. Throughout the magazine’s pages, certain topics seem to crop up again and again: the eternal quest for better sleep, advice around sex and relationships, ways to manage stress, and more.

In fact, some stories shared years and even decades ago seem more relevant than ever. We took a moment to look into the rearview mirror at some of these larger themes, the better to see them through our present lens.

Yoga Topics Then and Now

From psychedelics to Pilates, these comparisons of cultural commentary prove that life is a constant (and cyclical) conversation.

Yoga and Pop Culture

If you can believe it, there was a time not so long ago that yoga was not considered mainstream in the U.S.

Then: Yoga’s introduction to the West began in the late 1800s, but it wasn’t until the early 1990s that yoga began to gain in pop culture popularity. Suddenly, yoga was everywhere. Celebrities including Sting (featured on a YJ cover in December 1995), Madonna, and Oprah touted the benefits of the practice; magazines began to feature the practice, noting its benefits in health and fitness columns; and it started to show up in movies and sitcoms. As our September 1998 article about yoga’s popularity put it: “After 5,000 years, yoga has arrived.”

Now: That mainstream celebration of yoga continues to this day. And if the yogis of the 90s were concerned about the glitz-ification of yoga, it’s unclear how they might feel about today’s landscape of hot yoga, influencer culture, and brand deals. It’s somewhat baffling to observe how far yoga has come in a few decades, and it’s only natural to ask the same question: when does yoga stop being yoga?

Marijuana and Psychedelics

Opening, stilling, and calming the mind are associated with yoga as well as certain mind-altering substances—so it’s only natural that the conversations should cross.

Then: The psychedelic undercurrents of the 1970s run strong through the initial issues of YJ—not only in explicit features and mentions, but in the artwork, figureheads, and overall feel. Hallucinogens seemed to dovetail nicely with the broader introduction of Eastern spirituality, each inviting participants to experience an altered state and a new perspective.

In the December 1980 issue, one writer considered the controversy around marijuana, chatting with scientists and spiritualists to debunk myths on both sides of the narrative. The piece ends with one quoted source saying he believes those under the persistent influence of marijuana are more susceptible to demagogues. (Big yikes.)

A decade later, YJ revisited the psychedelic boom of the ‘60s, asking pioneers of that movement to share what they had learned in the decades since. The general takeaway? Drugs offer temporary access to a level of consciousness that can be more authentically and sustainably tapped via yoga, meditation, and ritual.

Now: Today, the general attitude around psychedelics is one of curiosity. Drugs including mushrooms and ketamine have even made their way into mainstream therapeutic practices, the guided trips helping humans access parts of the subconscious and process past events. The current rationale behind these drugs seems to tend toward individual benefit rather than the societal overhaul of the 60s.

Although still contentious in some parts of the world, marijuana use is pretty openly accepted at this point. Cannabis is now legal in 24 states, Canada, Uruguay, and Mexico, with dispensaries as common as coffeeshops in some cities. There are even 420-friendly yoga classes. And although regular LSD trips may have fallen out of favor, spiritual seekers still gather to trip out and sit in ceremony, more recently with the help of ayahuasca, a psychedelic plant with ancient roots in South America.

Aging

The conversation around aging—slowing it, avoiding it, even attempting to erase it—has evolved in major ways over the last 50 years, for better and for worse.

Then: Yoga is all about acceptance, which includes the very human process of getting older. A 1995 YJ cover story featuring Ram Dass, titled “Be Old Now,” highlighted this pursuit. At that time, Dass was championing a movement he called “spiritual eldering,” which reframed aging as yet another opportunity for spiritual growth.

A few years later, an editor noted a shift in the connection between yoga and aging. Rather than acceptance or an opportunity to become stronger mentally and physically, the image of yoga seemed to be offering an escape from mortality. One quote from the September 1998 issue of YJ, in reference to yoga in pop culture, encompasses this well. “There’s a subliminal message contained in all of these images: that if you do enough Sun Salutations you won’t have to grow old and die.”

Now: Aging looks different now than it has at any other point in history—literally. Scientific strides and a collective want of longevity mean that growing old is less about loss and more about what we can maintain as the years pass. Yoga plays a part in this, aiding in mobility and strength for practitioners of any age. But perhaps Dass’ sentiment is one that we should be reminded of: growing old is an adventure and a privilege, not something to be avoided entirely.

Yoga for Athletes

Yoga is a physical activity unto itself, but it also supports athletes of all kinds—pretzel poses not required.

Then: In the late 70s and early 80s, yoga was beginning to be touted as a helpful tool for athletes looking to stretch it out. Yoga Journal’s July 1978 issue was entirely dedicated to sports, with insights and practices offered for marathon runners and swimmers, an essay about the mindfulness inherent in playing baseball, and tips on utilizing yoga to prevent joint trauma. In 1983, the magazine shared tips for hikers and backpackers looking to stay limber on outdoor journeys and more present on the trail.

Now: These days, yoga is intrinsically tied to most sports and the focus remains on both the physical and mental benefits. Surfers, runners, golfers, climbers, cyclists, skiers, and anyone seeking physical strength all find support through yoga. (Plus, the NFL player to yoga teacher pipeline is very real). The practice eases not only minds and the potential for injury, it invites a stronger connection to the breath, and it typically results in quicker recovery from injury. On both the personal and professional level, yoga is recognized not only as a complement to athletics but a standalone practice unto itself.

Pilates

Before Pilates became a full-on social craze, there were the practices Pilates was based upon.

Then: With all of its modern-seeming mechanics, Pilates may seem new, but the founder of the fitness movement was actually born in 1880. Joseph Pilates drew inspiration for his unique practice from Zen meditation, yoga, and the exercise routines of Greeks and Romans, ultimately creating a fitness practice that drew on breath control and mental acuity (think stabilization and precision). It gained in popularity throughout the 1980s and 90s and was featured in the November/December 1994 issue of YJ, which saw former managing editor Linda Sparrowe attending several reformer classes and delving into the history of Pilates and its ties to yoga.

Now: Pilates is having a major moment. The phrase “Princess pilates” pulls up nearly 70 million posts on TikTok, most of which focus on the aesthetic of present tense Pilates (pink and put-together) along with actual practices. These days, Pilates is usually touted as a route to a toned, lithe physique rather than the functional movement practice of the 90s. As a bonus, recent studies have proven Pilates’ potential to ease symptoms of depression and anxiety. And if you want to try the strengthening workout without sacrificing your yoga routine, there’s always the hybrid approach: yogalates.

Gurus and Scandal

The exploitation and corruption of power—whether committed by a guru, a politician, or charismatic leader of any sort—is nothing new. Still, the way we grapple with these realities evolves.

Then: In the mid 80s, YJ asked the broad strokes question, “What makes spiritual teachers go renegade?” The piece went on to explore whether or not these spiritual teachers are “enlightened,” cite possible connections between that state of mind and radical behavior, and offer a series of possible explanations that let these gurus, at least in part, off the hook. Oh, and the next article in the issue profiled Ma Anand Sheela, the spokesperson for Rajneesh (also known as Osho), who you may remember from Netflix’s 2018 cult documentary Wild Wild Country, so there’s that.

Now: The #MeToo movement of 2016 sparked an ongoing conversation around the prevalence of sexual harassment and assault. In so doing, it shines a spotlight on all sorts of subcultures—including that of the yoga world, including the disgraced “gurus” of Western Kundalini as well as ample allegations against Bikram Choudhury and the late K. Pattabhi Jois. As past mistreatment continues to be addressed and new truths come to light, the upshot of the situation is an increased awareness and a higher bar for behavior. Although allegations of abuse, assault, and mistreatment are far less tolerated today than in recent decades, they continue to occur. We still have work to do in ensuring there are no new incidents, although the community is more primed to hear, share, and reckon with this abuse rather than allowing such claims to remain an open secret.

Environmentalism

The quest to protect the planet is inherently tied to yoga. You know, mindful living and all.

Then: The evolution of the environmental movement is loosely chronicled in YJ’s pages, dating back to its earliest days, with references to humans’ connection with nature and our need to protect the planet. It wasn’t until the 1990s when talk of the hole in the ozone, rainforest depletion, and other topics sparked mainstream conversations as well as YJ covers dedicated to the cause.

In one 90s feature, YJ outlines how to be an “earthwise consumer,” foreshadowing the societal lean toward sustainable products, clothing, food, and more. Several years later, another article called for a spiritual response to the ecological ravaging of the planet, inviting readers to practice “Earth yoga.” The idea was to awaken a connection with nature, honor the planet with heightened awareness (environmental and otherwise), and, ultimately, help restore the Earth.

Now: Despite the best efforts of those dedicated yogis, extreme weather has become the norm the world over. Mindfulness around consumption, and the ability to maintain your center amid constant existential chaos, is essential—and, hence, so is yoga. Conversations around how yoga studios can bolster community after natural disasters, as well as how the practice can offer mental and emotional soothing in the face of environmental devastation, are just some of the ways yoga supports our environmental realities.

Online Yoga

Yoga is huge in cyberspace. In fact, it’s sort of difficult to imagine a world in which your yoga or meditation practice isn’t a mere click away.

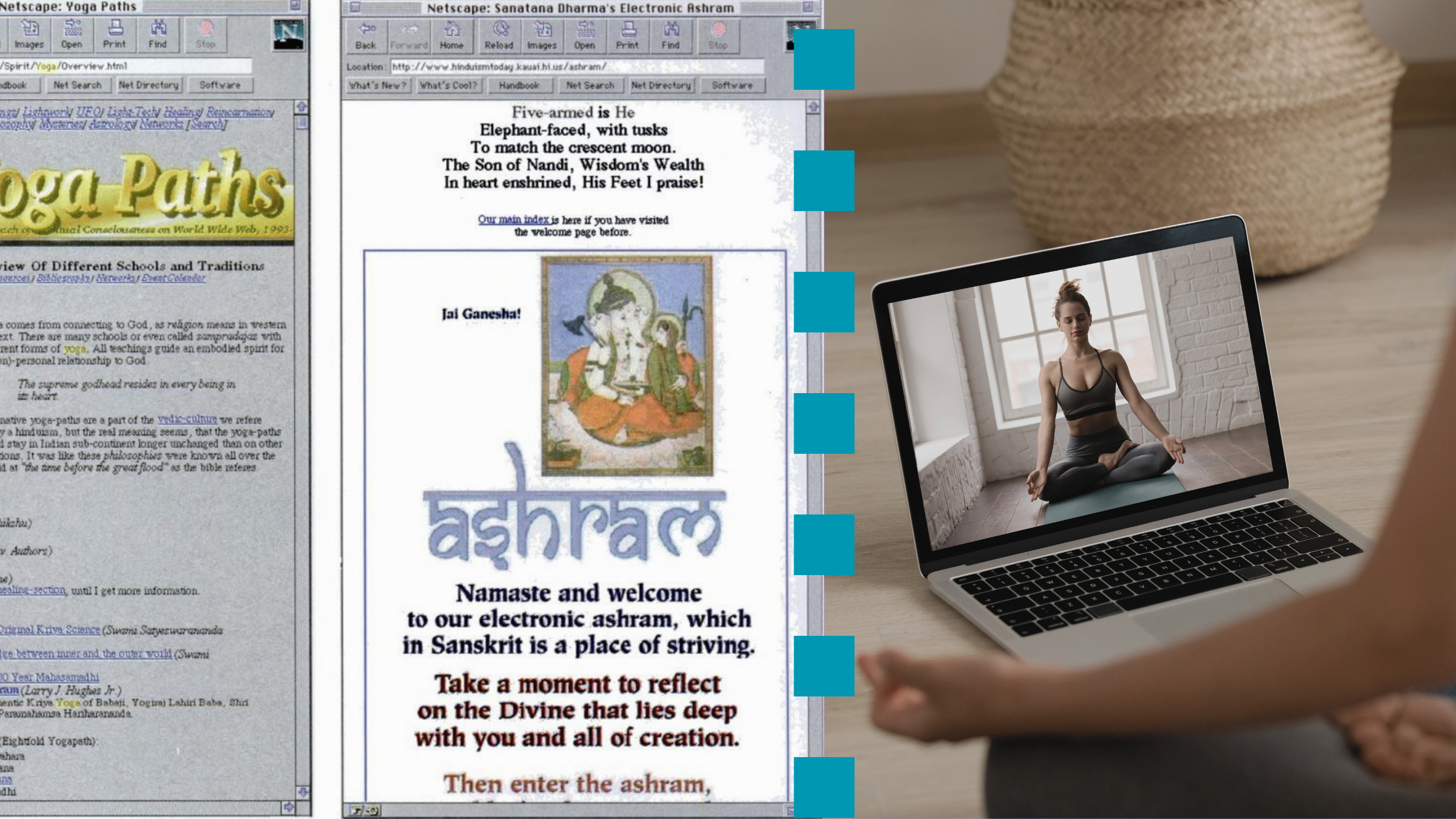

Then: “Will going online connect us or disconnect us from our spiritual quest?” That important question was posed in the April 1996 issue by Jeff Zaleski, who went on to be the publisher and editor of Parabola magazine. At the time, Zaleski called the advent of interconnectedness an “online spiritual gold rush,” citing access to copious information and online communities (Deadheads were apparently early adopters).

He goes on to describe what Yahoo is, how to use it, and the yoga sites you’ll find there. He was also careful to note that the Internet is without prana, or embodied presence. This was, of course, long before social media, not to mention AI.

Now: Three decades later, there are hundreds of thousands, if not millions, of sites dedicated to yoga. Given the proliferation of online classes, virtual teacher trainings, social media influencers, and digital media outlets (like us!), contemporary yoga owes a lot to the connection offered by the online world.

But we’re still asking the same question: does the Internet make us more or less connected to the spiritual world? The answer is probably both—and we should probably continue to ask the question.

Yoga Retreats

Just as yoga traveled to the West from the East, the West has consistently looked to take its spiritual explorations elsewhere—including back East.

Then: Yoga travel began as trips to the practice’s origins in India, where devotees could learn from gurus and experience full immersion in the philosophy as well as the poses. But yogis are often free spirits, and free spirits love to explore. In 1983, years before yoga was an everyday word, our first guide to yoga vacations and retreats featured destinations in the US, Canada, and Mexico. (California boasted the longest list of options by a landslide.) Though many of the listings were package retreats, the article also included places where readers could organize low-budget group gatherings of their own.

Now: Yoga retreats today exist largely in the luxury space. Teachers regularly schedule gatherings all over the world, inviting attendees to take a week or weekend to escape the grind, practice and meditate on the regular, and explore the local environs. (Yoga summer camp is even a thing!) Prices may have risen, but value has, too, with getaways taking place against dreamy destination backdrops. That said, it’s still essential to do your retreat research and understand your and your guides’ “why.” Intention is key.

This article is part of our look back at the last 50 years of yoga in commemoration of Yoga Journal’s 50th anniversary. Here’s where you can read more.