If you buy through our links, we may earn an affiliate commission. This supports our mission to get more people active and outside.Learn about Outside Online's affiliate link policy

Yoga in the 2020s: Pandemic, Personal Practice, and Progress

(Photo: Getty; Vanessa Compton)

Throughout America’s obsession with yoga the last half century, our perception and interpretation of it has changed considerably with each decade. We’re barely halfway through the 2020s yet already there’s been tremendous and unexpected shifts in where and how and why we practice. As we navigated a transition to practicing from home and then a return, for some, to the studio, other changes that had been building for decades began to finally take hold. The following article explains all that and more as part of Yoga Journal’s 50th anniversary coverage of yoga’s evolving role in America throughout the 1970s, 1980s, 1990s, 2000s, 2010s, and 2020s.

The year 2020 will go down in history as the year a home yoga practice became the collective norm.

There was little choice in the matter. By late March, schools, workplaces, stores, restaurants, gyms, and yoga studios had shut down in compliance with state and federal orders due to the pandemic. Isolated at home and anxious about the future, many found it challenging not to idle away those long days of lockdown in a state of perpetual fear or funk.

But you know what helps quiet anxiety and counter persistent negative thinking? Yoga.

Within hours of stay-at-home orders taking effect, many yoga studios quickly adjusted. Although some teachers were already teaching on various online platforms, those who weren’t quickly learned how to upload a class to YouTube, livestream on Instagram and Facebook, or figure out Zoom.

It was a chance to support students with the sequences, meditation, and breathwork they were accustomed to practicing. It was also an attempt at restoring some sense of normalcy, routine, and community to everyday life.

It worked. Americans started practicing yoga and meditation at home in unprecedented numbers. Memes related to dropping into Child’s Pose in grocery store aisles or staying in the pose indefinitely showed up everywhere, including the pages of The New Yorker. Equal parts relatable, sad, and darkly humorous, they helped anchor yoga even more firmly in the culture of the moment.

Yoga became so pervasive that in the months following the initial shutdown, YouTube’s Yoga With Adriene saw her channel’s popularity surge by more than a million new subscribers. Before the end of the year, The New York Times Magazine had dubbed its creator, Adriene Mishler, the “reigning queen of pandemic yoga.”

We needed yoga in 2020, and yoga was there for us. We understood that. What we didn’t understand was how pervasively this time would influence our experience of yoga in the years ahead.

How Our Yoga Practice Changed

For most of us, 2020 started as a fairly normal year. Practicing yoga online had been availabe for some time, although it was typically considered optional. Then everything changed. When we were stuck at home, an online practice became essential.

In addition to YouTube, there were apps, including Asana Rebel, Alo Moves, Glo, Yoga Vibes, Udaya Yoga, Yoga Anytime, Down Dog, Gaia, and Daily Yoga. There were pose how-tos and practice videos on Yoga Journal as well as other sites. There were on-demand platforms where individual teachers shared classes behind a paywall.

Those of us who had previously practiced in group classes experienced yoga differently at home. Without mirrored walls or studios crowded with strangers, there was less self-consciousness. Simply showing up to practice became more of a priority than worrying whether our alignment was precise or our pre-pandemic mani-pedi was still passable.

There were other conveniences to practicing at home, including skipping traffic, sneaking in a quick practice while working from home, and not needing to worry if your most presentable leggings were in the laundry. Also, the ease of access to online resources meant it was easy to explore of different styles of yoga. A vinyasa regular might check out yin yoga. Someone who had only previously taken restorative yoga might explore a beginner’s hatha class. And if the style didn’t jive with you, it was easy to click off after a few minutes. The ability to access class with anyone from anywhere on the planet also helped shift our attention—and, in some instances, reverence—away from a small number of yoga celebrity and influencer teachers of the previous decades.

And unlike in-person studio classes, at-home yoga didn’t necessarily demand an entire hourlong commitment. Micro yoga practices, lasting anywhere from five to 30 minutes, made yoga even more approachable. It’s no surprise that the YouTube channel Yoga With Kassandra, which already had hundreds of classes that were 30 minutes or less, saw its number of subscribers triple during the pandemic. These on-demand—and by demand—practices continue to proliferate years afterward. If there’s one thing we learned thanks to the pandemic, it’s that some yoga is better than no yoga.

But there was no yoga studio as a sanctuary. We lacked the nuanced instruction, shared community, and overall experience of studio classes. Even if a teacher gave verbal adjustments, it was unlikely they could see the actual correction. And the lonely reality was that even if you were “in” a class of a hundred people, the second you closed your computer, you were back in your home, alone. As Tara Stiles, founder of the once in-person studio and now primarily online platform Strala Yoga reminds her students, “Online is great. In person is magic.”

Our uncertainty about the world coupled with the stress of being confined to close quarters taught us to access yoga in real time by slowing our breath, quieting our thoughts, and sitting with our discomfort, on and off our mats.

What 2020 Meant for Yoga Teachers and Studios

Overnight, the landscape had also completely shifted for teachers and studios. Historically, independently owned yoga studios tend to run on tight profit margins. Many studios were already struggling even more in the late 2010s after expanding their class schedules in response to increased demand for yoga.

For some teachers, the move online was incredibly lucrative, much more so than when they taught in person. They could draw more than 40 students to a class with a suggested donation of $10 as opposed to making $40 a class in a studio. Yet many career yoga teachers were left without reliable revenue. Contract workers without salaries or health insurance, they took crash courses in online teaching to support students and to pay the rent.

When only modest numbers of students returned to in-person classes after the pandemic, many studios increased rates yet still found it impossible to remain in business. Close to 30 percent of yoga studios shut down by the end of 2021, including the in-person locations of YogaWorks, one of the largest chains worldwide. Some industry trackers estimate that by early 2023, up to 50 percent of studios in the US had permanently closed.

What The Early 2020s Taught Us

As society reopened, some students made their way back to studio classes, others kept their online subscriptions, and many availed themselves of both. At the same time how we practiced yoga changed, so did why we practiced. In a significant departure from past decades, the number one response yoga practitioners cited for coming to the mat in 2022 was stress, according to a survey by Yoga Alliance. Prior to the 2020s, the most common reason was flexibility.

Following years of relentless emphasis on fast-paced vinyasa and #yogaeverydamnday, the yoga space had seen a surge of interest in slower styles including restorative yoga, yin yoga, and yoga nidra even prior to the pandemic. These were welcomed by many who turned to them for calm in the face of relentless uncertainty in 2020. Rest as a cultural imperative was needed and more people were opting for that in our yoga practice.

“People were really getting interested in how the practice affects the nervous system,” explains Judith Hanson Lasater, restorative and Iyengar yoga teacher and co-founder of Yoga Journal. There was no shortage of scientific research that supported how yoga, meditation, and breathwork supported physical, psychological, and emotional well-being.

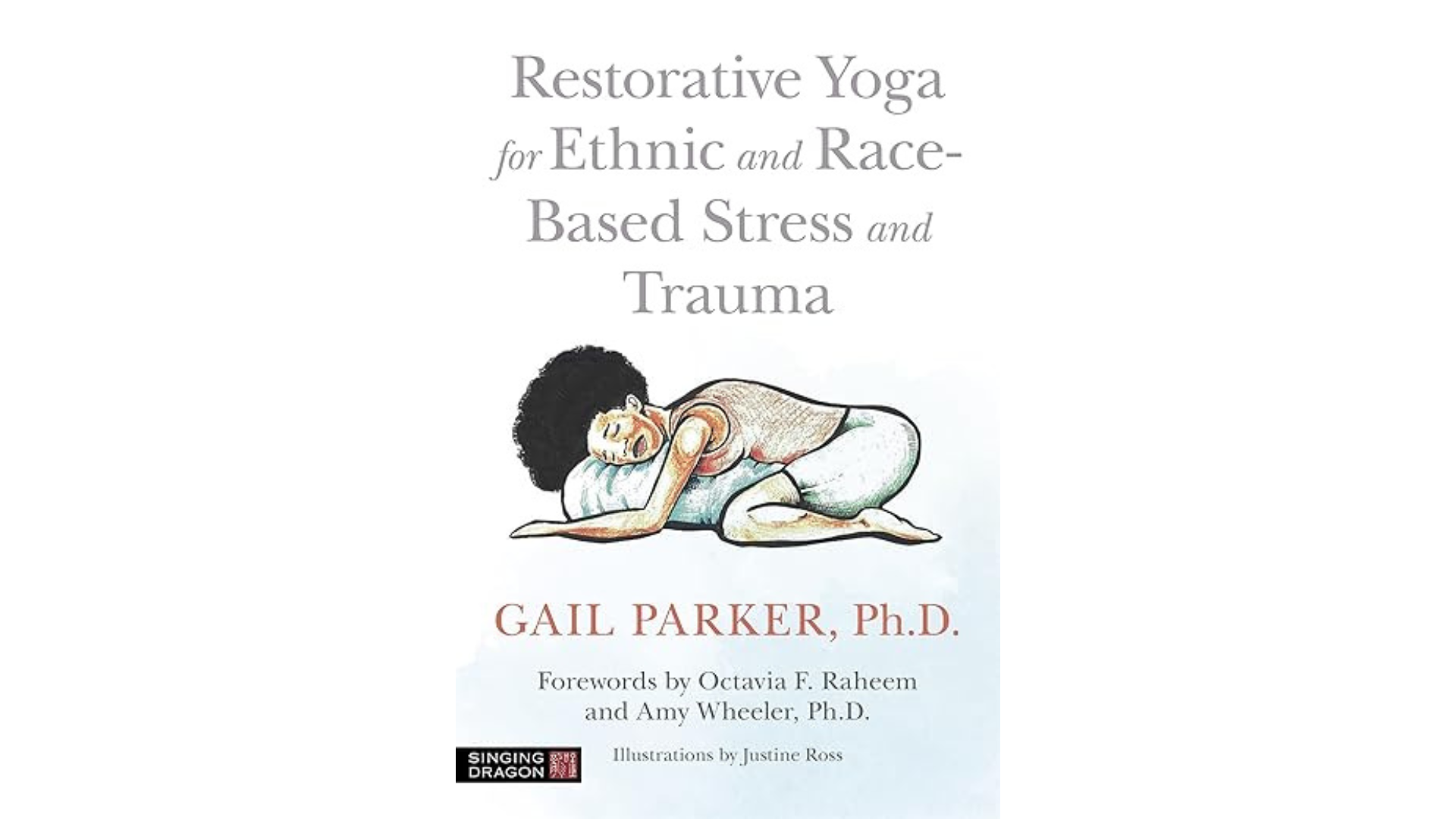

There was also ample research indicating the profound role these practices play in helping address the symptoms of complex post-traumatic stress disorder (c-PTSD). In August 2020, psychologist and yoga teacher Dr. Gail Parker published her first book, Restorative Yoga for Ethnic and Race-Based Stress and Trauma, months after the tragic death of George Floyd. “When we practice Restorative Yoga, we are teaching our nervous system how to release contraction and to feel safe coming into deep states of rest that support repair, rejuvenation, and resilience,” wrote Dr. Parker. “When we learn to experience our emotional pain and discomfort without contracting around it and reacting to it, and instead just let it move through us, our nervous system becomes regulated and we become emotionally regulated.”

By early 2021, teacher Tracee Stanley had published Radiant Rest: Yoga Nidra for Deep Relaxation and Awakened Clarity and in early 2022, we benefited from Octavia Raheem’s book Pause, Rest, Be: Stillness Practices for Courage in Times of Change.

At the same time, interest in meditation was growing exponentially, with more than 2,500 meditation apps launched since 2015. By the end of 2020, the Calm app had more than 100 million downloads and the number of registered users for the Headspace app reportedly doubled from 2020 to 2021. Following the return to in-person education, an increasing number of schools started allowing for quiet time during the day, regardless of whether or not they refer to it as “meditation.”

It was a time of constant flux. And, with the help of yoga, we were learning to navigate it.

Leveling the Practice Space

The terms inclusive and accessible began to be used increasingly in the yoga space in recent years. As more people were curious to try yoga, the practice needed to evolve and become more accessible for every body. The concerted effort to help students slowly gained momentum following teacher Jivana Heyman’s launch of Accessible Yoga, a training platform for teachers, in 2007.

Teaching accessible yoga means finding a version of a pose that works for an individual’s body. This can be achieved through normalizing the use of props or sharing variations for poses without referring to them as “less than” the traditional expression. With an increased emphasis on creating a welcoming and accepting space, terms such as “advanced” and “full expression of a pose” began falling out of the yoga lexicon and were replaced with language that doesn’t emphasize achievement and reminders to pay less attention to how a pose appears and more awareness on how it feels in the body. These were significant changes that had started in previous years yet sputtered. The changes, however, have recently taken hold in various styles of yoga.

The early part of the decade also saw the practice become more inclusive through studios that were safe spaces for everyone. Teacher Jordan Smiley opened Courageous Space in Denver, Colorado, in 2020 as a safe space for the transgender and nonbinary community to practice yoga.

And in 2021, yoga teacher Danni Pomplun launched HAUM in San Francisco’s Mission District. His intention was to bring yoga to the LGBTQ+ community. “At HAUM, we believe everyone deserves to experience the transformational journey of coming home to who they truly are,” Pomplun explained in a letter posted to the website. A year later, HAUM opened a second location in Haight-Ashbury.

In 2021, yoga teacher trainings had become increasingly crowded and, some asserted, distanced from their origins. Around that same time, Arundhati Baitmangalkar launched her podcast, Let’s Talk Yoga. A self-described immigrant and Indian yoga teacher, Baitmangalkar decided to create a podcast “to inspire other yoga teachers of color.” In so doing, she also made the yoga teaching space more thoughtful by sharing the perspective of someone who understands both the nuances of tradition and the shortcuts of contemporary life—and isn’t afraid to take sides when discussing topics. The podcast continues to bring the kind of straight talk that many in the yoga space had been saying was needed.

The Yoga Industry

All those people practicing yoga at home during 2020 shifted not only how the US practices yoga but how many of us come to the mat. Some 16 percent of the adults, approximately 40 million people, reported practicing some form of yoga, according to a 2022 survey by the Centers for Disease Control.

That translates to a lot of dollars spent on yoga mats, apparel, classes, workshops, apps, wellness retreats, and yoga teacher trainings—approximately $21 billion worldwide. That number has been projected to double by 2032.

At the same time, sustainability has reached unprecedented levels in the yoga industry. Some companies continued their existing and longstanding efforts, such as Jade Yoga planting a tree for every mat sold and sourcing natural rubber as the primary material. Other brands, such as Manduka, introduced new ones, including launching an “Almost Perfect” line of mats with modest blemishes available at a discount rather than discarding them at cost to the company and the planet.

Apparel companies, including Girlfriend Collective, have not only been relying on recycled fabrics but partnering with platforms that allow their customers to resell previously loved items on their site or sell them back for credit toward the next purchase.

Looking Ahead

The experience of the pandemic helped us understand how we could turn to yoga to quash anxiety, yet the years following that have been teaching us much more. Throughout the early 2020s, we have been learning yogic principles as applied to everyday situations. It’s a quiet resurgence of interest in what yoga actually means. Despite the imperfections of the way the practice exists in culture, we are fortunate to exist in a time in which so many have access.

Perhaps as online offerings continue to share unprecedented access to yoga, new ideas about practicing and teaching will meet old ones as we continue to evolve our approach to the practice. Through what we collectively experience and learn, we will continue to find that yoga has even more to offer the many.

Photos and illustrations, clockwise from upper left: Foreigner bassist and meditator Jeff Pilson: Roy Rochlin | Getty; Man in Child’s Pose: ljubaphoto | Getty; Woman in Camel Pose: Vanessa Compton; Lou Reed: Hudson River Wind Meditations (vinyl reissue); Couple: F G Trade | Getty; Cell phone with meditation app: Catherine Falls Commercial | Getty; Coco Gauff: Al Bello | Getty; Woman in kneeling side stretch: AnVr | Getty; Older adult yoga class: Karen E. Segrave Photography; Yoga Pant Nation book cover; Man stretching in wheelchair: Vanessa Compton; Woman practicing yoga outside: Don Arnold | Getty; Sesame Street Yoga Pose print by Mindful & Co.; Restorative Yoga for Ethnic and Race-Based Stress and Trauma by Dr. Gail Parker book cover; Woman with tattoo carrying yoga mat: FG Trade Latin | Getty; Game Changers article design by Yoga Journal and illustration by Alvaro Tapia Hidalgo; Woman practicing yoga at a “Beyond Monet” art exhibit: Xinhua News Agency | Getty; Woman practicing Pyramid Pose with blocks: Vanessa Compton; Woman meditating: Getty; AcroYoga couple; Woman folding forward with blocks beneath her hands: Andrew Clark for Yoga Journal.