Raised on Yoga

I remember the first time I worked up the courage to bring one of my friends, a lanky 12-year-old named Jimmy, to the ashram our family went to on Sundays. It was the early ’90s, and in the suburbs of Sacramento, California, having yogi parents like mine was about as common as being raised by wolves. I was in junior high—identity fluctuating like the stock market—and I never mentioned yoga to my classmates, ever. They found out about it anyway—”India, man, that’s a long drive,” a friend once remarked—but I’d already taken flak for my strange name, the photos of bearded South Asian men on our walls, and the lack of Doritos in our pantry. I didn’t need any extra questions like “What’s that, like, yogurt thing your parents do again?”

But Jimmy seemed different. We did martial arts together, and I hoped that he’d make the connection between our Bruce Lee obsession and a morning of Om-ing, meditation, and stretching. It seemed worth a try, anyway, and I invited him to come along. I remember a feeling of peace washing over me as Jimmy and I sat in the meditation hall listening to a man named Ananda read the Bhagavad Gita. Jimmy seemed to be enjoying the whole scene—a room full of people sitting cross-legged, chanting to a harmonium, and nibbling on dried fruits. And after all was said and done, Jimmy said the meditation stuff was “pretty cool.”

I was elated by the thought that I’d finally found a spiritual buddy. But on Monday at school, Jimmy changed his tune. “Dude, Jaimal took me to his parents’ voodoo cult,” I heard him reporting to our group of jockish friends. “That was, like, the trippiest experience of my life.” Everyone laughed. “Don’t your parents eat seaweed or something?” another asked. I played along; I was used to this. “Yeah, I hate going to that place,” I said. “It’s so boring.” I laughed, but inside I felt troubled. I’d have to stick to my original game plan, keeping the depth I’d discovered in my parents’ yogic and Buddhist practices hidden from view.

When I was growing up, yoga was still on the fringe—a hippie or New Age tradition. There were no mainstream studios to speak of. Most of us had to go to ashrams to learn about yoga—places where the sights, sounds, and experiences were so unlike the rest of American life, you felt a bit like you’d stepped across the threshold to a foreign land or even another planet. To many minds this unfamiliar terrain had all the trappings of a cult.

Most of us early American yoga brats (let’s say from the 1960s into the early ’90s) tagged along, not always voluntarily, on our parents’ spiritual adventures, randomly picking up a good vibe or two but completely unsure of how to integrate the practice into our lives. For starters, the entire culture gave us not-so-subtle messages that this yoga stuff wasn’t cool, so we weren’t even sure we wanted to embrace the practice. And our own parents were probably unable to give us much guidance. A bit like immigrants in this vast new land, most of them would take years to figure out how to assimilate the practice into daily life. Yoga was often both a joyful adventure and an unsettling one for the entire family.

Change of Heart

These days, yoga—especially asana—is part of the cultural norm. It has made its way into every nook and cranny of American life: Football players have adopted the practice as a way to keep themselves injury free and agile. Executives are learning to meditate in their boardrooms. Hollywood celebrities hire private yoga teachers and flaunt beaded malas, scarves with images of Hindu deities, and T-shirts with slogans such as “Karma,” as if those accessories were haute couture. “It’s taken 3,000 years,” goes the joke in urban yoga circles, “but yoga is finally hip.”

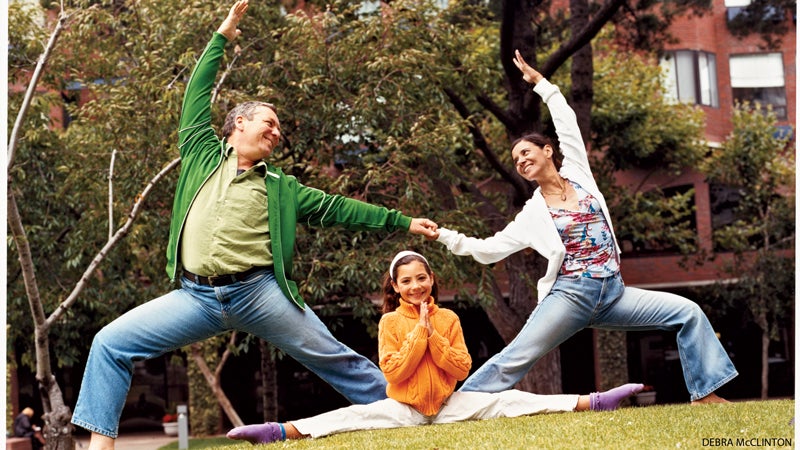

So, not surprisingly, growing up in a yoga family today isn’t really weird at all. Lots of parents are embracing yoga’s physical, spiritual, and philosophical practices and are exploring how to bring them out into the world. They squeeze in a few minutes of meditation before everyone else is awake and the demands of school lunches and carpools beckon. They practice asana with toddlers around their mat. They grapple with how to model satya (truthfulness) for their kids when they’re tempted to tell a white lie. And their kids are picking up on it, wanting to mimic the ancient practices, just as they mimic the cooking, gardening, and other activities their parents do.

Of course, there are classes for kids now, too, and many are more than just an alternative to after-school sports. Jodi Komitor, who grew up doing yoga with her parents on Fire Island in New York, founded Next Generation Yoga in Manhattan, the country’s first yoga studio for kids and families. (She has since moved it to San Diego.) She says the number of parents introducing their kids to yoga has increased exponentially over the past decade, and not just as a way of keeping them flexible for soccer and gymnastics.

Komitor teaches animal poses and games during family classes, but she hits psychological and spiritual notes, too. She asks family members to whisper affirmations in each other’s ears, or has them sit and chant Om together. “Because so many parents practice yoga now,” says Komitor, “families seem to be comfortable with both levels of teaching. The bonding that goes on in the classes is astounding.”

Finally, yoga is overcoming its reputation as a mysterious, foreign, and fringe activity and now often coexists happily with traditional American life. In many circles, yoga is deeply influencing cultural values, and families are at the forefront of making this happen.

Rebel Yell

Yoga teachers Lisa and Charles Matkin of Garrison, New York, are representative of today’s American yoga family: They were both raised by yogi parents and are passing on the practice to their two children, Tatiana and Ian. But it took time and effort for both Charles and Lisa to fully embrace the spiritual practice of yoga they now pass on to their children.

Like the Beatles and the Beach Boys, Charles Matkin’s grandparents began practicing yoga under the famous Maharishi Mahesh Yogi, founder of the international Transcendental Meditation movement. Charles was raised in Maharishi’s 4,000-person yogic community in Fairfield, Iowa, where he began a daily meditation and asana practice around the age of 10. His memories are fond ones. OK, so maybe he was jealous of his superflexible sister, and he did sometimes get tired of his mom nagging him—”Did you meditate today, Charles?”—but overall, he loved practicing with his family and treasured the support of the community. “We practiced asana and meditation together,” Charles remembers, “but it was much more than that. We were so close. It was just an incredible way to grow up.”

But as in any such community, there were different interpretations of what it meant to be a yogi. Some people appropriated the accouterments of a romanticized Indian culture—for example, shedding Western clothes in favor of white lungis (long, skirtlike garments for men) was fashionable in those days. When Charles was 15, he and his friends began to ridicule people who chose the outer trappings to the detriment of an internal practice. “They were trying so hard to appear peaceful on the outside, they wouldn’t express their feelings and ended up acting out in weird ways,” Charles says with an understanding chuckle. “They’d greet with you with ‘Namaste,’ but they’d say it clenching their teeth.” Eventually, like most teenagers, Charles rebelled against his roots. “I stopped meditating,” Charles says. “That was my rebellion. Instead of smoking crack, I stopped meditating.”

He also realized that many people in his community were using meditation and asana to run away from emotions instead of attending to them. This seemed to be the antithesis of yoga, a practice that encourages witnessing all aspects of life—the beautiful and the difficult—from a place of nonattachment. So, he left Iowa and his practice behind for a brief period and took up acting in New York. “I thought actors really explored their feelings and I wanted to do that, too—to be around people doing that,” he says. It didn’t take long for him to realize that actors could also fall into their own emotional traps, by creating drama and putting on false emotions. From that point on, he focused his meditation on observing his emotional world rather than running from it. Decades later, this approach is at the heart of his teaching, and he attempts to pass it on to his own children.

“I try to emphasize that yoga and spirituality won’t fix your emotional life,” he says. “They’re incredible tools. But you can meditate to numb your feelings, too, and that gets you nowhere. I think meditation works best when you use it to see more clearly what’s going on inside, so you can act from a more balanced place.”

Past Perfected

Charles’s wife, Lisa, was introduced to yoga at a young age, too, and like Charles and countless others who spent their youth sitting beside parents in a meditation hall, she rebelled before she made yoga her own as an adult—in her case as an alternative to the alcoholism and eating disorders she struggled with as a young fashion model. “Yoga saved me,” Lisa says, remembering how a single yoga class, after decades away from the practice, motivated her to get clean and become a yoga teacher herself.

But it has taken more than asana for Lisa to find her way. After years of regular yoga practice and abstinence from alcohol, she relapsed into drinking after the birth of her first daughter. The birth reawakened memories of sexual abuse, and she fell into a deep postpartum depression. Lisa soon realized that only doing yoga was not enough for her. She went through counseling and found that, like Charles, she’d been using yoga to run away from her feelings instead of digging into them and eventually letting them go. “It was really difficult, but I realized that I’d never felt the pain of that abuse and that I had to face it. I’d been trying to avoid ever feeling bad. I had to feel it if I was going to get through it.”

Lisa hopes that the yoga path will help her children cope with life’s challenges in a positive way. The Matkins are devoted to carving out a path—a blend of Eastern spirituality and Western psychological “processing”—that works for their family. They attempt to honor the subtle nuances of how yoga and emotions interact, and they bring this perspective into their family life. “Of course, we strive for ahimsa,” says Lisa, “but we also know that sometimes we’re going to get angry, and that’s OK. I try to give feelings that I used to judge as negative the space and time to offer their teachings. I don’t try to shove them away and act more spiritual than I am in any given moment.”

One thing the kids probably won’t have to ever-so-skillfully process is feeling like outcasts for having two yoga teachers as parents. “It’s kind of the opposite,” Charles says. “Tatiana’s friends come over, and they all want to learn yoga. They all know what it is, and most of them have done it. Tatiana is at the age where she wants her mom’s yoga teachings all to herself. She gets jealous that they are being shared with her friends.” Even young Ian spontaneously teaches his preschool class yoga poses—or more specifically, the freeze-tag yoga-pose game the family often plays at home—and both of the children like to take turns teaching a part of their parents’ home yoga retreats.

I used to hide my Buddha statue and tofu sandwiches from my friends, so it astounds me that kids are asking their parents for yoga. In Berkeley, California, yoga teachers Scott Blossom and Chandra Easton are raising a daughter, Tara, who sees yoga studios on every block. “Honestly,” Chandra tells me, “so many of our friends are yoga teachers, or at least do yoga, I think our daughter feels more normal than the kids whose parents have nine-to-five jobs.”

But kids don’t always want to do yoga with their parents, and Tara has made it clear that she wants yoga to be her own thing. When she was five she marched into the home yoga room and declared, “Mom, I want to take my own yoga class.” Her mother was surprised and recalls that “ever since she was born, I’d been inviting her into our home yoga room to practice with me. But I understood, too. She wanted to be independent.” So, Tara happily went to a kids’ yoga class for a while, before moving on to what’s hot this year—trapeze arts, “a more playful yoga,” Scott says.

While Scott and Chandra don’t regularly teach Tara asana at home, they do invite her into their spiritual rituals, which combine several traditions: Scott, who leans toward Hindu mysticism, and Chandra, a Buddhist meditator and Tibetan translator, teach Tara their own mix of Buddhist and Hindu spirituality. Before bed, Scott reads Tara some of the Ramayana, an Indian epic, and then recites her two favorite Krishna Das chants—Hanuman Chalisa and Shivaya Namaha—as she falls asleep. “My intent is to read her myths and sing the associated songs and chants that have been celebrated for millennia. These stories, like all mythologies, have a psychic potency for inspiring values like courage, devotion, kindness—and revealing the unlimited potential of our mind and spirit,” Scott says.

He and Chandra have also set up a small shrine in Tara’s room with a few little deities. “We call this ‘kiddie puja,’?” says Scott, referring to the daily ritual of worship. As part of the puja they leave a sacred offering of dried fruits and chocolate that Tara gets to eat the following morning. “This gives her a positive association with the whole process,” he says. Still, even with all of the Eastern influences that surround Tara, she has a mind of her own. Much to their surprise, “it’s actually baby Jesus that Tara seems to like the best,” Chandra says with a laugh. “She is a free thinker.”

Parental Mentors

Scott also teaches Tara self-observation, which is at the heart of all yogic practices. In asana the inquiry is: What effect does a certain pose have on how you feel? In diet (following Ayurvedic teachings) the inquiry is: What effect does a certain food have on how you feel? Scott has taught Tara to be aware of the subtleties of food since she started eating, and he says she can already identify when a food makes her produce too much mucus or irritates her digestion. “She knows which days to stay away from dairy or bread,” says Scott. “It surprises me how much she understands the causative

relationship.”

Parents like Chandra and Scott, and Charles and Lisa, have the support of other yogi parents around them (unlike my mom, who tried to steer me away from Kool-Aid and other junk foods. She eventually cracked under pressure and let me frequent Carl’s Jr. for its chicken bacon cub sandwich, so as not to give me a complex about being so different from my peers). Even better than that, these yogic parents have mentors. “We’ve learned so much from watching Ty.”

Sarah Powers raise their daughter,” says Chandra, referring to the well-known yoga teachers who are based in Marin County, California, who are about a decade ahead of Scott and Chandra on the parental learning curve. “I’m not sure we would feel as confident without seeing them take a yogic approach and really succeed.”

Sarah feels strongly that maintaining a consistent practice of her own has enabled her to parent her daughter Imani in a conscious way. “My practice helps me to listen deeply before assessing and reacting to things,” she says. “A child doesn’t just learn by what you do; they also learn from the quality of your presence with them.” It’s these qualities of calm, patient presence and aware communication that Sarah and Ty have valued more than anything else. They’ve never pushed Imani into practicing asana with them. Instead, they have modeled yogic behavior and incorporated yoga’s principles into their family life. As Sarah puts it, “Yoga has been in the fabric of the way she’s been raised, even if we didn’t always label it as yoga.”

During Imani’s first year, Sarah and Ty rarely put her down or in a stroller—they always made sure someone was holding her. “We consciously kept her bonded to us and by extension to the whole human family,” Sarah says. As a result, Sarah has observed that Imani has grown up confident and secure about meeting new people and being in new situations. “Her cellular memory remembers being connected, so she doesn’t feel like an outsider; she feels connected to the world,” she says.

Sarah and Ty made the decision to homeschool Imani after a visit to her kindergarten class showed the teacher rewarding the children who repeated lessons quickly and ignoring the children with a more reflective style. For the Powers, homeschooling meant that they could encourage their daughter’s innate curiosity while honoring the natural rhythms of each day. So, instead of rushing to eat breakfast and catch a bus, Imani started each day in a contemplative way: Her daily ritual was to wake up and sit quietly in her parents’ laps as they meditated.

Sarah and Ty weren’t concerned that Imani would feel socially estranged as a result of homeschooling. She always engaged in numerous extracurricular activities, and she became a professional dancer at a young age. When Imani decided to attend public high school for a year to try the so-called normal route, she pulled straight As. Her only problem with traditional school was that all the other kids seemed unmotivated, and Imani didn’t like being the only one who enjoyed homework. She studied dance in Paris for her sophomore year in high school, and she’ll be skipping her junior and senior years to attend Sarah Lawrence College in New York. Her parents got word from Paris that she’s started teaching yoga to one of her French friends. “Are we

proud?” Sarah asks. “Yes, you could say that. It was a sort of experiment, but we’re happy to see that the yogic way we’ve raised her has helped her flourish and be a content human being.”

Sometimes I can hardly believe that the “trippy” thing my parents did, the word I was afraid to mention at recess, is now part of just about every city in America, not to mention across the Atlantic. But confirmation comes nearly every day. I might overhear a couple of businessmen talk about making “good karma investments” or watch a high school football team practice vinyasa at the 50-yard line. I won’t say I’m not jealous of the yoga brats born more recently. But after talking with other yoga family members, I’ve started to think of myself as something of a pioneer. A couple of years ago, I even ran into Jimmy while visiting my mom. We caught up on the usual stuff, and then out of the blue he told me he had some new things going on in his life:”I’m taking a really cool yoga class,” he said. I didn’t get the impression that he’d made the connection between his class and that ashram experience, and I didn’t mention it. But I like to think I planted a tiny seed.

Jaimal Yogis is a writer in San Francisco and the author of Saltwater Buddha.