If you buy through our links, we may earn an affiliate commission. This supports our mission to get more people active and outside.Learn about Outside Online's affiliate link policy

Jivana Heyman Has a Revolutionary Idea: Make Yoga Accessible to Everyone

Heyman in his garden, where he tends to his plants and takes time for reflection. (Photo: Ian Spanier)

In the soft 7:30 a.m. Santa Barbara sun, Jivana Heyman walks down the green wooden steps into his backyard garden. He admires the herb bed where lavender, oregano, and thyme flourish. Scratching his short auburn beard and adjusting his glasses, he moves on to what he calls his “three favorite W’s”: watering, weeding, and wandering. Many living things in his personal oasis call for his attention: prolific lemon and orange trees, an eggplant-and-pepper patch, an itinerant inedible fig tree that he can’t seem to bring himself to cut down. As he tends to them, he takes time to think. This space for reflection is part of what Heyman, founder of the nonprofit organization Accessible Yoga Association and author of Accessible Yoga, loves so much about gardening.

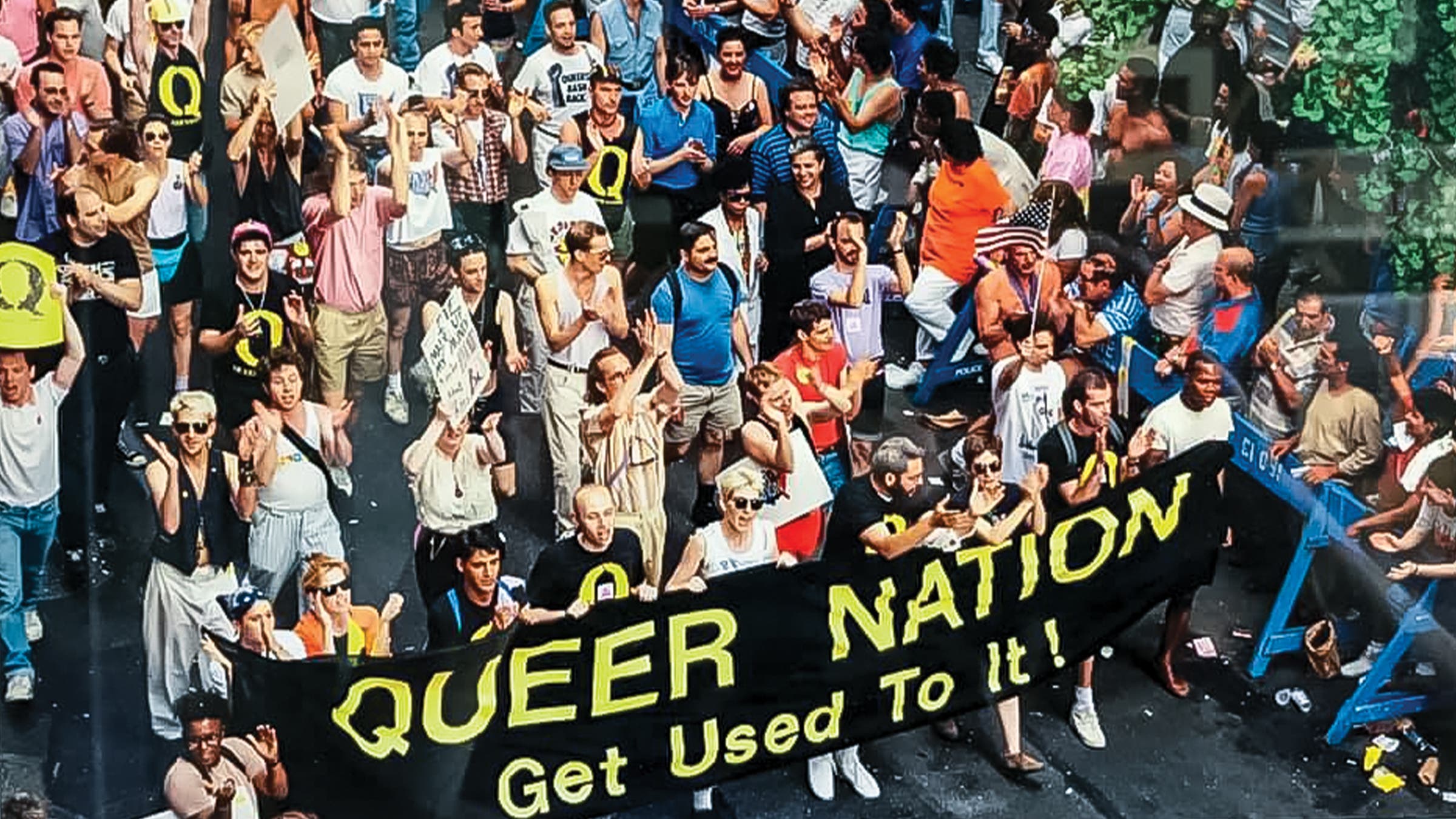

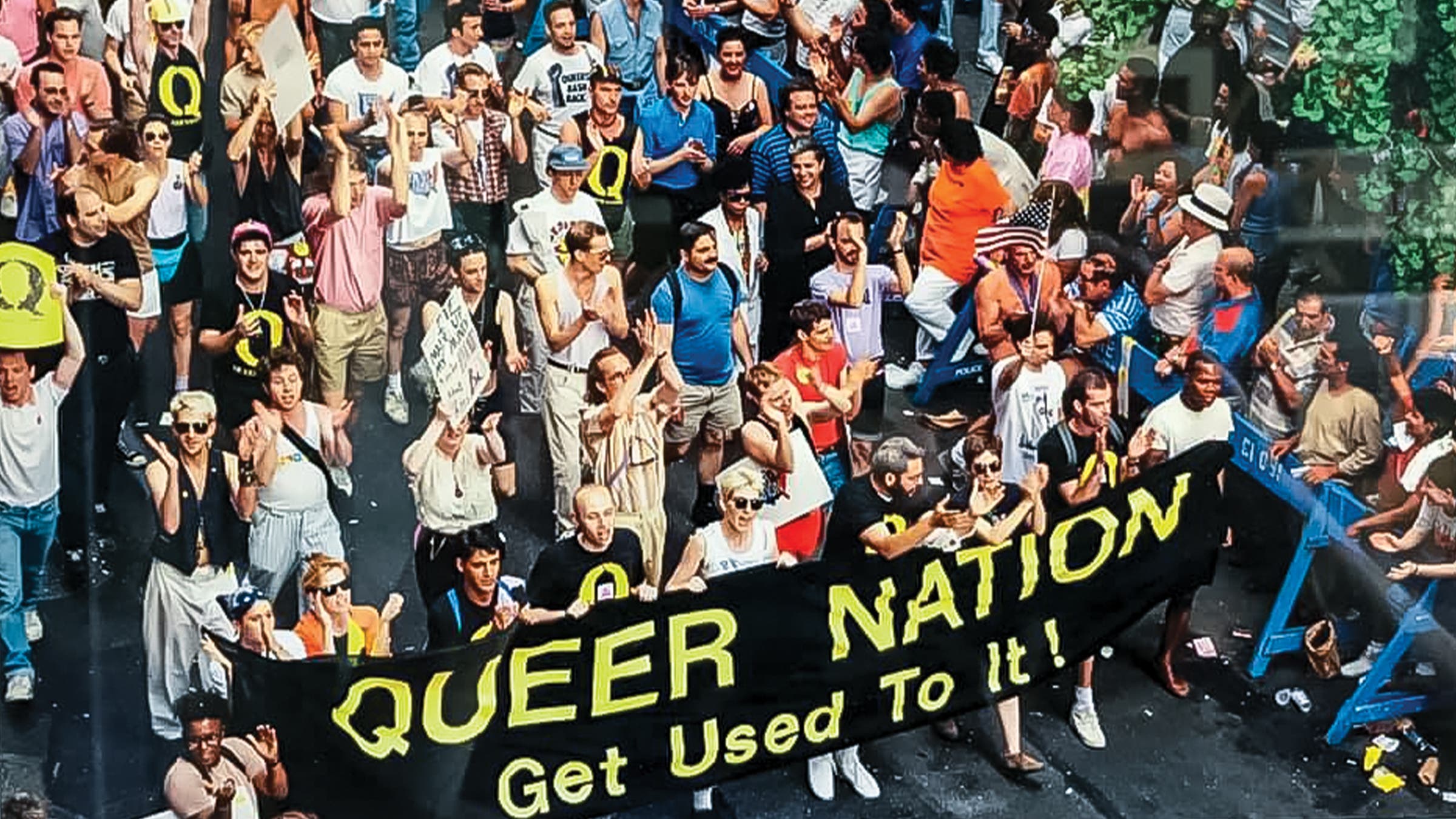

Heyman sits down at the table on his back porch. He pulls up some old snapshots on his phone and laughs wistfully at one, taken at a 1990 march associated with the New York City Gay Pride Parade. In it, Heyman, in his mid-20s, clad in white and wearing sunglasses, marches behind a banner. His hands are lifted enthusiastically in mid-clap.

In some ways, the calm yoga teacher and father of two grown children bears little resemblance to the fiery activist in the photo. But Heyman is still passionate about making change, and the fire that stoked the ardent young demonstrator still burns brightly. The focus of the flame has just shifted. Now, he is committed to making yoga accessible to everyone.

Finding Yoga

In the early 1990s, Heyman was living in San Francisco, the epicenter of the AIDS epidemic. People all around him were dying—his best friend, former lovers, and many close friends. Heartbroken, angry, and afraid, he joined the HIV/AIDS activism group ACT UP to protest the lack of accessible, affordable treatment.

“I was completely overwhelmed and in grief,” Heyman says. “It was horrific. I was partying, drinking, and demonstrating. I desperately needed help.”

Heyman was literally sick with sorrow; he started having digestive issues. He visited the woman who would become his mentor, Kazuko Onodera, for a massage. “She had a picture of Swami Satchidananda—who was also my grandmother’s yoga teacher—on her wall.” When he mentioned that connection, she invited him to take one of her yoga classes. Over the next few years, Onodera taught him not only yoga, but also cooking and gardening. “She understood the fullness of the practice,” Heyman says. “She saved me.”

As Heyman delved deeper into yoga, he stopped partying and drinking and started volunteering at a local AIDS hospice. In 1995, he received his yoga certification and began teaching classes for people living with HIV/AIDS and those suffering from the grief of losing loved ones to the disease. “I wanted to bring people together who were isolated and lost and struggling,” he says. His classes started with an hour-long check-in session, followed by 60 minutes of asana. “It was like a support group. The check-in session was the yoga to me.”

Yoga allowed Heyman to process his feelings and grieve his friends’ deaths. It also helped him become emotionally mature enough to enter a loving, stable relationship: “I thought, ‘I’m ready to settle down, yoga is calming me down, and I’m ready to be with someone healthier.’” He met his husband, Matt Fratus, through ACT UP in January 1993; they were married on August 31, 1997, at the Integral Yoga Institute of San Francisco.

As yoga studios multiplied exponentially in the early to mid-2000s, a desire to build an alternative yoga community began to bubble up in Heyman. “It felt like a lot of us were left out—that we were the outsiders,” he says. He had been teaching yoga to people with disabilities since 1995.

“Over the years, I saw how dedicated many of my students were and I kept trying to get them to take the 200-hour teacher training programs I was running,” Heyman says. “But they often felt that teacher training wasn’t accessible to them. It finally dawned on me that I could make the teacher training program accessible for them.” In 2007, he developed a program to train those students to be teachers themselves.

Heyman started using the name Accessible Yoga to create an inclusive yoga movement welcoming to people of all abilities, financial circumstances, ages, races, and identities.

Accessible Yoga can take the form of chair yoga. It can be demonstrating pose variations that allow those with osteoporosis or arthritis to participate. It can also be accepting “a busy mind” rather than encouraging a quiet one—a supportive action to resist neurotypicality and support mental health and mental diversity. Accessible Yoga might be diffusing the competitive spirit among yogis that can develop during a class by allowing advanced poses without paying special attention to them.

“Yoga is a spiritual practice, and the whole idea of yoga is that the same spirit exists in all of us, so if it’s not accessible, it’s not yoga,” Heyman says.

Watch: Chair Yoga As a Practice of Radical Inclusion

A Community Connects

In 2013, Heyman and Fratus moved to Santa Barbara. “The hardest thing about moving away was leaving my yoga community and students in the Bay Area,” Heyman says. He felt a profound sense of isolation, with no friend network in his new city. One day while meditating, he had an epiphany. He came to consciousness realizing that he should plan a conference that would bring all the “outsiders” together.

“I was already teaching and adapting yoga for people with disabilities, but the conferences were another side—more community building, more counterculture,” Heyman says. “When I started talking about the idea, people came out of the woodwork; everyone wanted to be part of it.”

That didn’t surprise Fratus, who had initially been drawn to Heyman’s enthusiasm and compassion when they volunteered together at ACT UP: “Jivana is passionate and magnetic. That makes it easy for him to rally people.”

The first conference, held in Santa Barbara in 2015, brought 130 members of the Accessible Yoga community together, including body-positive yoga teacher Dianne Bondy and yoga teacher Matthew Sanford, who specializes in adapting yoga for people living with disabilities. (He became paralyzed in a car accident at age 13.)

“It felt like a family reunion, even though we didn’t know each other,” Heyman says. In 2015, Heyman officially cofounded the Accessible Yoga Association, and the group began to run conferences and appoint ambassadors.

Breathing into Being

One evening in 2017, Heyman was walking to the car with his husband when he felt a sudden tightness in his chest. He couldn’t breathe. Positive he was having a heart attack, he asked Fratus to drive him to the emergency room. The ER doctors ran countless tests to determine the source of his symptoms, but they all came back negative.

“The doctor said, ‘I think it’s an anxiety attack,’” Heyman says. “I laughed and said, ‘I’m a yoga teacher, I can’t have anxiety.’”

In hindsight, Heyman says that his anxiety attack made perfect sense. His mother had recently died. “Seeing her struggle to open her eyes to even say goodbye to her grandchildren was heartbreaking,” he says. Her loss, coupled with recent struggles in his relationship with his daughter, pulled him into a deep depression. After his anxiety attack, he found that pranayama itself was a struggle. Traditional pranayama and focusing too much on his breath triggered additional anxiety. “I hadn’t been really dealing with my stuff, so I had to go back and start over with my practice,” he says.

He began to ask himself how he could be more self-compassionate in his practice, instead of pushing himself to be perfect and strong. “I felt like I didn’t know what I was doing at the most elementary level of practicing yoga,” he says, “and it brought up a lot of imposter syndrome for me and insecurities as a teacher. It has taken me years to get comfortable working with my breath again.”

Over the next few years, he also deeply reexamined yoga philosophy and what it meant to his practice. “I began to consider the relationship between my practice and the suffering in the world,” he says. For example, he realized that ahimsa wasn’t just about living a mostly good life.

“In its active form, ahimsa is compassion, love, and connection,” Heyman says. “[Nonharming] means actively working to reduce other people’s suffering. Yoga is about getting out of your head long enough to realize that it’s not really about you. The story you’re telling yourself, where you’re the main character, is fiction. To experience the nonfiction version of reality we need to actively practice ahimsa—to engage in yoga as service.”

See also: What Yoga Philosophy Helped Me Understand About Anxiety

The Rainbow Connection

A revolution is defined as a fundamental, paradigmatic change in the way of thinking about or visualizing something—a sea change, a radical shift. And it’s what Heyman thinks is necessary for yoga in America. “It’s time to address the dissonance between mainstream practice and the depth of yoga’s teaching,” he says.

In the Bhagavad Gita, Arjuna faces the question “Should I act?” Heyman encourages us all to confront this same challenge. Seva should extend beyond the yoga sangha and into the broader community, he says, “embracing acts of service that see, care for, and uplift those around us, without losing sight of your own path and your own self-care.”

In other words, get out there and do the volunteering, the community building, the grassroots action, the elevating of others, and the thought work. The COVID-19 pandemic has given Heyman hope that this change is possible: “Pre-COVID, the way that studios were set up, only the well-known teachers—who were mostly white, non-disabled, and thin—got paid to teach.” Now, he sees a more diverse set of teachers, different options for making classes financially accessible, and classes being available online. Going forward, he would like to see South Asian teachers honored, hired, and paid what they’re worth for their knowledge, teaching, and expertise.

In Heyman’s new book, Yoga Revolution: Building a Practice of Courage & Compassion, he writes about a concept he calls the “rainbow mind”—a fierce commitment to inclusivity, accessibility, anti-racism, openheartedness, and courage, with a nod to the queer significance of the rainbow. Just as light refracts into a rainbow through a prism, Heyman believes yoga shows us how our lives are all different and diverse, but in our hearts we’re all connected.

“We all have the capacity to serve in our lives,” he says. “You don’t have to do something spectacular, but you can take care of your child in a kind way or respond to your partner with love rather than with sharpness. When you’re feeling centered or taken care of because you’ve been able to find a connection with yourself, you cause less harm and can be more loving. Yoga is meant to give you courage.”

More from Jivana: 6 Ways to Avoid Ableism in Yoga Classes

Dakota Kim is a writer, editor, and recovering restaurant owner living in Los Angeles. Her stories have appeared in the Los Angeles Times, the New York Times, Salon, Food & Wine, Travel + Leisure, and many other publications.

Finding Yoga

In the early 1990s, Heyman was living in San Francisco, the epicenter of the AIDS epidemic. People all around him were dying—his best friend, former lovers, and many close friends. Heartbroken, angry, and afraid, he joined the HIV/AIDS activism group ACT UP to protest the lack of accessible, affordable treatment.

“I was completely overwhelmed and in grief,” Heyman says. “It was horrific. I was partying, drinking, and demonstrating. I desperately needed help.”

Heyman was literally sick with sorrow; he started having digestive issues. He visited the woman who would become his mentor, Kazuko Onodera, for a massage. “She had a picture of Swami Satchidananda—who was also my grandmother’s yoga teacher—on her wall.” When he mentioned that connection, she invited him to take one of her yoga classes. Over the next few years, Onodera taught him not only yoga, but also cooking and gardening. “She understood the fullness of the practice,” Heyman says. “She saved me.”

As Heyman delved deeper into yoga, he stopped partying and drinking and started volunteering at a local AIDS hospice. In 1995, he received his yoga certification and began teaching classes for people living with HIV/AIDS and those suffering from the grief of losing loved ones to the disease. “I wanted to bring people together who were isolated and lost and struggling,” he says. His classes started with an hour-long check-in session, followed by 60 minutes of asana. “It was like a support group. The check-in session was the yoga to me.”

Yoga allowed Heyman to process his feelings and grieve his friends’ deaths. It also helped him become emotionally mature enough to enter a loving, stable relationship: “I thought, ‘I’m ready to settle down, yoga is calming me down, and I’m ready to be with someone healthier.’” He met his husband, Matt Fratus, through ACT UP in January 1993; they were married on August 31, 1997, at the Integral Yoga Institute of San Francisco.

As yoga studios multiplied exponentially in the early to mid-2000s, a desire to build an alternative yoga community began to bubble up in Heyman. “It felt like a lot of us were left out—that we were the outsiders,” he says. He had been teaching yoga to people with disabilities since 1995.

“Over the years, I saw how dedicated many of my students were and I kept trying to get them to take the 200-hour teacher training programs I was running,” Heyman says. “But they often felt that teacher training wasn’t accessible to them. It finally dawned on me that I could make the teacher training program accessible for them.” In 2007, he developed a program to train those students to be teachers themselves.

Heyman started using the name Accessible Yoga to create an inclusive yoga movement welcoming to people of all abilities, financial circumstances, ages, races, and identities.

Accessible Yoga can take the form of chair yoga. It can be demonstrating pose variations that allow those with osteoporosis or arthritis to participate. It can also be accepting “a busy mind” rather than encouraging a quiet one—a supportive action to resist neurotypicality and support mental health and mental diversity. Accessible Yoga might be diffusing the competitive spirit among yogis that can develop during a class by allowing advanced poses without paying special attention to them.

“Yoga is a spiritual practice, and the whole idea of yoga is that the same spirit exists in all of us, so if it’s not accessible, it’s not yoga,” Heyman says.

Watch: Chair Yoga As a Practice of Radical Inclusion

A Community Connects

In 2013, Heyman and Fratus moved to Santa Barbara. “The hardest thing about moving away was leaving my yoga community and students in the Bay Area,” Heyman says. He felt a profound sense of isolation, with no friend network in his new city. One day while meditating, he had an epiphany. He came to consciousness realizing that he should plan a conference that would bring all the “outsiders” together.

“I was already teaching and adapting yoga for people with disabilities, but the conferences were another side—more community building, more counterculture,” Heyman says. “When I started talking about the idea, people came out of the woodwork; everyone wanted to be part of it.”

That didn’t surprise Fratus, who had initially been drawn to Heyman’s enthusiasm and compassion when they volunteered together at ACT UP: “Jivana is passionate and magnetic. That makes it easy for him to rally people.”

The first conference, held in Santa Barbara in 2015, brought 130 members of the Accessible Yoga community together, including body-positive yoga teacher Dianne Bondy and yoga teacher Matthew Sanford, who specializes in adapting yoga for people living with disabilities. (He became paralyzed in a car accident at age 13.)

“It felt like a family reunion, even though we didn’t know each other,” Heyman says. In 2015, Heyman officially cofounded the Accessible Yoga Association, and the group began to run conferences and appoint ambassadors.

Breathing into Being

One evening in 2017, Heyman was walking to the car with his husband when he felt a sudden tightness in his chest. He couldn’t breathe. Positive he was having a heart attack, he asked Fratus to drive him to the emergency room. The ER doctors ran countless tests to determine the source of his symptoms, but they all came back negative.

“The doctor said, ‘I think it’s an anxiety attack,’” Heyman says. “I laughed and said, ‘I’m a yoga teacher, I can’t have anxiety.’”

In hindsight, Heyman says that his anxiety attack made perfect sense. His mother had recently died. “Seeing her struggle to open her eyes to even say goodbye to her grandchildren was heartbreaking,” he says. Her loss, coupled with recent struggles in his relationship with his daughter, pulled him into a deep depression. After his anxiety attack, he found that pranayama itself was a struggle. Traditional pranayama and focusing too much on his breath triggered additional anxiety. “I hadn’t been really dealing with my stuff, so I had to go back and start over with my practice,” he says.

He began to ask himself how he could be more self-compassionate in his practice, instead of pushing himself to be perfect and strong. “I felt like I didn’t know what I was doing at the most elementary level of practicing yoga,” he says, “and it brought up a lot of imposter syndrome for me and insecurities as a teacher. It has taken me years to get comfortable working with my breath again.”

Over the next few years, he also deeply reexamined yoga philosophy and what it meant to his practice. “I began to consider the relationship between my practice and the suffering in the world,” he says. For example, he realized that ahimsa wasn’t just about living a mostly good life.

“In its active form, ahimsa is compassion, love, and connection,” Heyman says. “[Nonharming] means actively working to reduce other people’s suffering. Yoga is about getting out of your head long enough to realize that it’s not really about you. The story you’re telling yourself, where you’re the main character, is fiction. To experience the nonfiction version of reality we need to actively practice ahimsa—to engage in yoga as service.”

See also: What Yoga Philosophy Helped Me Understand About Anxiety

The Rainbow Connection

A revolution is defined as a fundamental, paradigmatic change in the way of thinking about or visualizing something—a sea change, a radical shift. And it’s what Heyman thinks is necessary for yoga in America. “It’s time to address the dissonance between mainstream practice and the depth of yoga’s teaching,” he says.

In the Bhagavad Gita, Arjuna faces the question “Should I act?” Heyman encourages us all to confront this same challenge. Seva should extend beyond the yoga sangha and into the broader community, he says, “embracing acts of service that see, care for, and uplift those around us, without losing sight of your own path and your own self-care.”

In other words, get out there and do the volunteering, the community building, the grassroots action, the elevating of others, and the thought work. The COVID-19 pandemic has given Heyman hope that this change is possible: “Pre-COVID, the way that studios were set up, only the well-known teachers—who were mostly white, non-disabled, and thin—got paid to teach.” Now, he sees a more diverse set of teachers, different options for making classes financially accessible, and classes being available online. Going forward, he would like to see South Asian teachers honored, hired, and paid what they’re worth for their knowledge, teaching, and expertise.

In Heyman’s new book, Yoga Revolution: Building a Practice of Courage & Compassion, he writes about a concept he calls the “rainbow mind”—a fierce commitment to inclusivity, accessibility, anti-racism, openheartedness, and courage, with a nod to the queer significance of the rainbow. Just as light refracts into a rainbow through a prism, Heyman believes yoga shows us how our lives are all different and diverse, but in our hearts we’re all connected.

“We all have the capacity to serve in our lives,” he says. “You don’t have to do something spectacular, but you can take care of your child in a kind way or respond to your partner with love rather than with sharpness. When you’re feeling centered or taken care of because you’ve been able to find a connection with yourself, you cause less harm and can be more loving. Yoga is meant to give you courage.”

More from Jivana: 6 Ways to Avoid Ableism in Yoga Classes

Dakota Kim is a writer, editor, and recovering restaurant owner living in Los Angeles. Her stories have appeared in the Los Angeles Times, the New York Times, Salon, Food & Wine, Travel + Leisure, and many other publications.