Heading out the door? Read this article on the new Outside+ app available now on iOS devices for members! Download the app.

Recent research suggests that yoga injuries are on the rise, but even the most devoted students among us practice for a mere fraction of the day. What we do the rest of the time—our posture and movement habits—has a far greater impact on our joints, muscles and fascia than our yoga practice.

So, while yoga might get the blame, sometimes a yoga pose is simply the straw that breaks the camel’s back, highlighting long-standing biomechanical imbalances created in our lives off the yoga mat.

Here are four common postural patterns to look out for, the poses or practices where they might set us up for increased injury risk, and some tips on how to re-create balance in the affected area.

See also Inside My Injury: A Yoga Teacher’s Journey from Pain to Depression to Healing

Postural Pattern No. 1: Upper Cross Syndrome and biceps tendonitis.

Ever felt a nagging ache at the front of the head of your shoulder after a few too many sun salutations? This could be related to a common postural habit known as upper cross syndrome.

The Anatomy:

Many of our daily activities, including driving and typing, involve our arms working in front of our body. This pattern tends to shorten and tighten our anterior shoulder and chest muscles (including pectoralis major and minor plus anterior deltoid) while weakening our posterior shoulder and mid back muscles (including the rhomboids, middle trapezius and infraspinatus). This imbalance pulls the head of the humerus forward in its socket.

When we take this altered position into weight-bearing poses, especially when our elbows are bent and gravity adds to the forward pull on the shoulders, we tend to lay on the biceps tendon (the tendon of the long head of biceps brachii) over the front of our shoulder joint. With repetition, the extra load on the tendon could create irritation and inflammation, leading to a niggling pain on the front of our shoulder.

Due to its repetition in yoga classes, Four-Limbed Staff Pose (Chaturanga Dandasana) is the most obvious pose to be aware of. Bent elbow arm balances can also be an issue, including Crow Pose (Bakasana), Eight-Angle Pose (Astravakrasana) and Grasshopper or Dragonfly Pose (Maksikanagasana). Even Side Plank (Vasisthasana) can irritate the biceps tendon if we allow the head of our weight-bearing shoulder to displace forward toward our chest.

See also Yoga Anatomy: What You Need to Know About the Shoulder Girdle

How to reduce shoulder injury risk:

• Soften chronic tension in your chest and anterior shoulders by incorporating both active and passive stretches for these muscles, such as humble warrior arms, reverse prayer position, or lying supine with arms out in a T-shape or cactus position (perhaps even with a rolled blanket or mat under your spine to create extra lift for your chest).

• Awaken your posterior shoulder muscles by utilizing arm positions that require active shoulder retraction or external rotation, such locust pose with T arm or cactus arm variations.

• Develop a more central weight-bearing position for the head of your shoulder in Chaturanga Dandasana by broadening your collarbones and turning your sternum forward. This position will be much easier to maintain if you stay higher in the pose, keeping your shoulders above elbow height. You might also consider skipping Chaturanga at times to build more variety into your yoga practice.

Postural Pattern No. 2: Lower Cross Syndrome and hamstring tendonitis

Another common yoga injury is pain in the proximal tendon of the hamstrings, where they attach to the sit bones at the base of the pelvis. This appears as a nagging, pulling pain just below the sit bones that often feels worse after stretching or sitting for long periods.

The Anatomy:

Most of us spend hours of each day sitting, and our soft tissues adjust to this habit. One such adjustment is the common muscular pattern called lower cross syndrome, where the hip flexors on the front of the pelvis and thighs (including the iliopsoas and rectus femoris) tend to become tight and the hip extensors on the back of the pelvis and thighs (including gluteus maximus and the hamstrings) tend to weaken, tilting the pelvis forward.

In yoga we often exacerbate this pattern by stretching our hamstrings far more often than we strengthen them. Over-stretching these weak muscles has the potential to irritate their tendinous attachment to the sit bones. The position of these tendons underneath the base of the pelvis also means that they are compressed every time we sit, potentially reducing their blood flow and making them slower to heal.

Every time we flex our hips, especially with straight legs, we lengthen the hamstrings. This makes the list of yoga poses to be aware a long one, including standing forward bends, seated forward bends, Extended Hand to Big Toe Pose (Utthita Hasta Padangusthasana), Pyramid Pose (Parsvottanasana), Splits (Hanumanasana), Standing Splits (Urdhva Prasarita Eka Padasana), Head to Knee Pose (Janu Sirsasana), Supine Hand to Big Toe Pose (Supta Padangusthasana), Downward Facing Dog, and others.

See also Get to Know Your Hamstrings: Why Both Strength & Length Are Essential

How to reduce your hamstring injury risk:

• Focus any hamstring stretches on the belly of the muscle. If you feel a stretch tugging on your sit bones when you stretch, move away from that sensation immediately by bending your knees or backing out of your full range of motion.

• Work on strengthening your hamstrings as often as you stretch them. Incorporate Locust Pose (Salabhasana) and Bridge Pose (Setu Bandha Sarvangasana) variations into your practice more often. You could also try stepping your feet a few inches further away from your torso in bridge pose to highlight hamstring contraction instead of glute contraction. Finally, keeping your hips square to the mat when you lift a leg behind you in Downward Facing Dog and the kneeling Balance Bird Dog Pose will highlight hamstring (and gluteus maximus) contraction.

Postural Pattern No. 3: posterior pelvic tilt and lumbar disc injuries

If you’ve ever had a lumbar disc rupture or protrusion—or been one of the 80% of adults that have experienced any kind of low back pain—you’ll remember how vividly aware you became of the movements and positions that put pressure on your spine, and how many of those appeared in the average class.

The Anatomy:

Our column of vertebra is connected by two moveable facet joints at the back of the spine and are sandwiched together by intervertebral discs at the front of the spine. When we lean back or take the spine into extension (a backbend), we load the facet joints; when we lean forward or flex the spine (into a forward curl) we load to the discs. If we fold more deeply forward, add weight by reaching with our arms, add sheering force by twisting the spine, or alter our pelvic position by sitting, we significantly increase the load on our discs.

Not all of us experience Lower Cross Syndrome; for some, slouching in our seat creates the opposite postural pattern, sending our pelvis into posterior tilt. The altered pelvic position has flow-on effects, one of which is to flatten the natural curve in our lumbar spine, bringing it out of extension into slight flexion. This means that in what we perceive as our neutral posture we are already adding extra load on our intervertebral discs, before we even start to fold forward, add weight, or alter pelvic position.

In healthy discs, adding load isn’t necessarily a bad thing, but if our discs are damaged or degenerating, the extra force we exert in a yoga practice could be the last straw that leads to disc injury, causing the jelly like protein filling of our disc to leak out, potentially irritating neighboring nerves as well as reducing spine function in that area.

Any poses or movements that load the spinal discs are worth paying extra attention to. This includes seated forward folds like Paschimottanasana and Head to Knee Pose (Janu Sirsasana), Seated Twist (Ardha Matsyendrasana), as well as yoga transitions to and from standing like those in sun salutations between Mountain Pose (Tadasana) and Standing Forward Bend (Uttanasana), and between a Low Lunge and Warrior I (Virabhadrasana I).

See also What You Need to Know About Your Thoracic Spine

How to reduce your disc injury risk:

The overall theme of reducing risk injury is to use your yoga practice to develop keener awareness of your posture. Once you know what a truly neutral lumbar spine and pelvis feel like, you can make a deliberate decision as to whether to add load to the discs by flexing the spine, rather than allowing your posture to make the decision for you.

• Using mirrors, photos, help from a friend, or the tactile feedback of the floor, wall, or a dowel stick behind your spine, practice creating neutral lumbar spine and pelvis in various orientations to gravity. Start supine (as in Savasana), progress to standing upright (Tadasana), then explore other standing poses like Extended Side Angle (Utthita Parsvakonasana) or Warrior III (Virabhadrasana III).

• Pay particular attention to what is required to create a neutral spine and pelvis in seated poses; that might include propping your sit bones on the edge of a blanket to lift them away from the floor and guide the pelvis out of posterior tilt into a neutral position.

• Learn to maintain a neutral lumbar spine in movements that load the discs as well. The transitions between standing and folding forward, and vice versa, place particular load on the lumbar; using your core muscles and legs to share the workload is hugely supportive for the spinal discs – a helpful habit to take off the mat as well.

Postural Pattern No. 4: “tech neck” and neck injuries

Smart phones and other devices have become a dominant part of our lives, but the hours spent looking down at a screen can have unintended side-effects. Forward head carriage, also called text neck or tech neck, is a common pattern these days, thought to be driven by the habit of looking down at phones and other devices for hours of every day.

See also Yoga We Know You Need: 4 Smartphone Counterposes

The Anatomy:

Tech neck is a common scenario where the weight of our head tilts forward from its natural weight-bearing position. Like all the postural habits discussed here, it can alter the biomechanical patterns around the spine, in this case placing additional load on the discs in our cervical spine. This could be an issue in any yoga pose but the stakes increase dramatically when we add body weight to the equation, as we do in certain inversions including Headstand (Sirsasana) and Shoulderstand (Salamba Sarvangasana).

It’s challenging enough to create a neutral spine when we turn the world upside-down for headstand; the challenge increases hugely if our perception of neutral is skewed to begin with. Taking forward head carriage into Headstand means carrying our bodyweight in a way our body—including our vulnerable discs—isn’t designed to do.

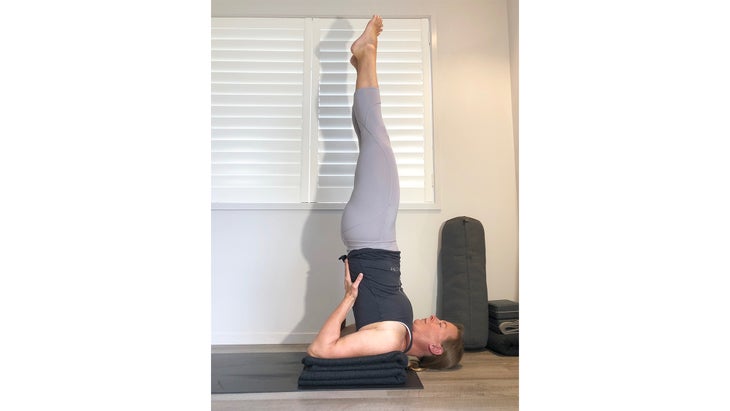

Shoulderstand is another controversial pose, taking the forward head position of text neck and adding bodyweight to it; given how common tech neck is in yoga students, some argue that the therapeutic benefits of this pose may no longer be worth the risk of it reinforcing existing dysfunction.

How to reduce neck injury risk:

As in posterior pelvic tilt, the core of neck injury prevention is re-education: learning anew what a neutral head and neck position look and feel like so that we can choose when and how we load the structures of our neck, rather than allowing unconscious habits to do that for us.

• Practice finding and maintaining neutral head and neck in various orientations to gravity, from supine using the feedback of the floor, to upright with a wall behind the back of the head, then progressing to unsupported positions like Tadasana, Triangle (Trikonasana), Downward Facing Dog and Dolphin Pose (Ardha Pincha Mayurasana).

• If you do wish to practice Headstand, invest time and effort in building improved muscular stability in your shoulders so that (while neutral head and neck position is still crucial) you are able to efficiently carry the bulk of the load in your arms instead of your head.

• If you enjoy practicing Shoulderstand, experiment with stacking blankets under your shoulders to reduce the degree of neck flexion required to create a straight line in the remainder of your body, or stay flexed in your hips so that you are able to support more of your bodyweight through your arms and hands and carry less in your head and neck.

Any physical activity has its risks and yoga is no exception. However, the recent rise in reported yoga injuries may be less a reflection of the practice, and more related to the habits we take into it. One of the great benefits of yoga practice is the opportunity it creates for reflection; rather than giving up on our practice because of the risks it could entail, we can choose to use it to become more aware of our posture, and more mindful in the way it influences us.

See also Yoga to Improve Posture: Self-Assess Your Spine + Learn How to Protect It